- OCD JOURNAL vol.4 no.1

- 2013.03.27

Unity of Sentiment and Scene: The

Associa- tion of Architecture with Landscape in Korea

1. Case one: Outdoor Pavilions, Study Halls and

Confucian Academies Traditional villages in Korea are divided largely into two types: those

inhabited mostly by people with one or two family names and those by people

with various family names. The former are clan villages, where the great

majority of residents belong to one or two clans and maintain a dominant voice

in the community through the generations. Confucianism had a remarkable influence on the formation and evolution

of clan vil- lages in Korea. As it took root as the governing ideology and

Confucian daily customs spread throughout Joseon (1392-1910) society, people

sharing the same ancestry began organizing clan groups around the head

families. In accordance with the Confucian world view which dominated everyday

life and rituals across social classes, the clan communi- ties erected

facilities necessary to manifest their noble status and maintain hierarchical

order within their clans. Among these facilities, outdoor pavilions (亭子, jeongja), study halls (精舍, jeongsa), and Confucian academies of advanced

studies (書院, seowon) are

included.

Confucian scholars believed that academic study was inseparable from

investigating the principles of nature. This is why traditional clan villages,

mostly built around the learned no- bility, have ancient pavilions, study halls

and academies where Confucian scholars read and studied the rules of nature as well as took rest, besides the residences

of the head families of leading clans. These facilities were built at scenic

places in and out of the village and beauti- fully harmonized into the natural

scenery. Study halls and pavilions provided the Confucian literati of Joseon with

ideal spaces to advance their studies and enjoy nature. These facilities are

simple buildings, normally consisting of a single open hall, but sometimes

containing an enclosed room. These mini- mal structures were designed to extend

the limited space of the buildings into nature, or bring nature into their

small but dignified spaces in nonchalant harmony. The Confucian literati of Joseon regarded the study hall as a place to

pursue their academic interests and express their views of nature and the world. They

believed they could empty their minds and enrich themselves in the humble halls. Hence they

are far from being authoritative elite-class architecture. Pavilions, built at scenic spots, were restful spaces where the literati

could contemplate nature and life. Initially intended as private places for elite

scholars, during the latter part of the Joseon period they became a kind of

public venue where people met for various purposes. They were used for family

or clan gatherings, or sometimes local literati meet- ings or parties for

seniors. Pavilions are mostly open structures with no walls, consisting of

pillars supporting a roof, so the surrounding scenery can be fully appreciated.

They were often built on higher ter- rain to look over the surrounding area, or

built on high stone bases, to command a better view. Pavilions and study halls in a clan village are products of the culture

of the local literati. The elite scholars based in rural villages built such

structures to enjoy natural landscapes and entertain guests, while seeking the

ultimate truth in nature. In other words, the pavil- ions and study halls

offered them places to practice the time-old principle of “investigat- ing

things and extending knowledge” (格物致知) as well as to

take free and leisurely ram- bles and recite poetry. In these unassuming

buildings the literati pursued their scholarly ideals and taught students,

instilling the values of integrity and modesty in the young generation. The architectural style of pavilions was also applied to Confucian

academies of ad- vanced studies (書院, seowon),

private educational institutions run by the provincial literati in their

hometowns during the Joseon period. These private academies had two primary

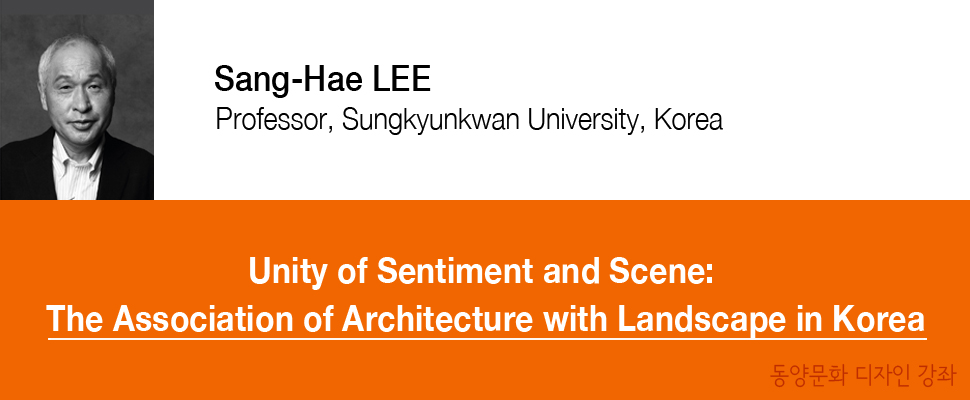

functions: teaching students and revering ancient sages. These private academies were built on scenic estates outside provincial

or county ad- ministrative seats, with low mountains at the back and a large

stream or sprawling fields in front. Ideally, they sat on a gentle slope facing a low mountain in

the distance across the fields, the buildings laid out in harmony with the

surrounding landscape. Generally they are found near places related with the

sages they honor. The academies were built at places of outstanding natural scenery

primarily because the Confucian scholars preferred to lead a reclusive life in

nature. They tried to cultivate body and mind amid nature to become one with

nature and heaven, the supreme state of mind in Confucianism. Therefore, the

Confucian scholars built their academies in scenic envi- ronments like a

mountain valley with a cool stream, where they could communicate with nature in

poetic language. The elevated pavilion was found to be the most appropriate architectural

form for this purpose. Scholars engaged in theoretic debate or held poetry

meetings at these pavil- ions, enjoying the surrounding landscape. In this way

they found escape from worldly pressures, resting and recharging themselves. The

elevated pavilion is usually the main entrance to a Confucian academy, or

sometimes a separate building inside the main gate. These academies

incorporating the Confucian world view into their architecture in a way

appropriate to the mountainous topography provided a new paradigm for Korean

archi- tecture. Among the Confucian Academies in Korea, Byeongsan Seowon (屛山書院, Byeongsan Academy) is one of the

representatives. The academy faces south from the foot of a ridge of Mt. Hwasan

(華山) with the

Nakdong-gang River flowing in front and Mt. Byeongsan (屛山) lying beyond the river, forming a picturesque

landscape. A broad sand beach spreads along the river and old gnarled pine

trees stand on the adjacent hill The view from the center of the lecture hall of the academy is truly

extraordinary. Mt. Byeongsan and the Nakdong-gang River and the blue sky come

into sight altogeth- er, beautifully framed between the pillars of Mandaeru (晩對樓) pavilion like a folding screen. It is an

ingenious spatial arrangement that gives the viewer the dramatic feeling of

being neither outside nor inside and yet becoming one with nature. Byeongsan Academy is highly evaluated for its architectural style

harmonizing with its beautiful natural environment. Walking amid the ancient

buildings or looking at the landscape from the lecture hall or pavilion in

front, it is easy to see how architecture can be integrated into the natural

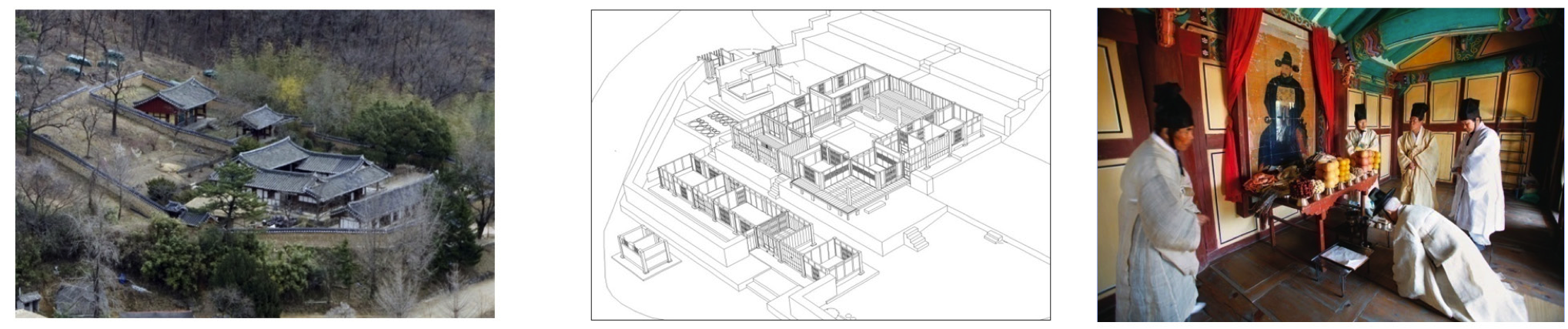

surroundings. 2. Case two: Changdeokgung Palace and Rear Garden From the Three Kingdoms period (37 BCE-668 CE) Korea’s royal palaces

were built to be modest but not shabby (儉而不陋), grand but

not extravagant (華而不侈). This tradi-

tion of Korean palace architecture is best manifested in Changdeokgung (昌德宮) Pal- ace. Of all the ancient palaces of Korea,

Changdeokgung is the one whose architecture and gardens best represent the

Korean aesthetic and the Korean use of space. The archi- tecture is created to

a friendly human scale, with the buildings and gardens following the natural

contours of the land. Changdeokgung Palace is composed of several major areas according to

function: the main court of administration where the ministers and officials

served the king; the court for government offices where the king and his

cabinet looked after politics; the residen- tial court where the king, queen

and other members of the royal family slept; and the Rear Garden where the

royal family went to rest and cultivate both body and soul. The architecture and Rear Garden of Changdeokgung Palace are neither

large in scale nor overbearing, and do not go against nature. The palace

attracts people with the under- lying charm of its sense of quietness and

intimacy. It has the power to entrance those who come in search of the beauty

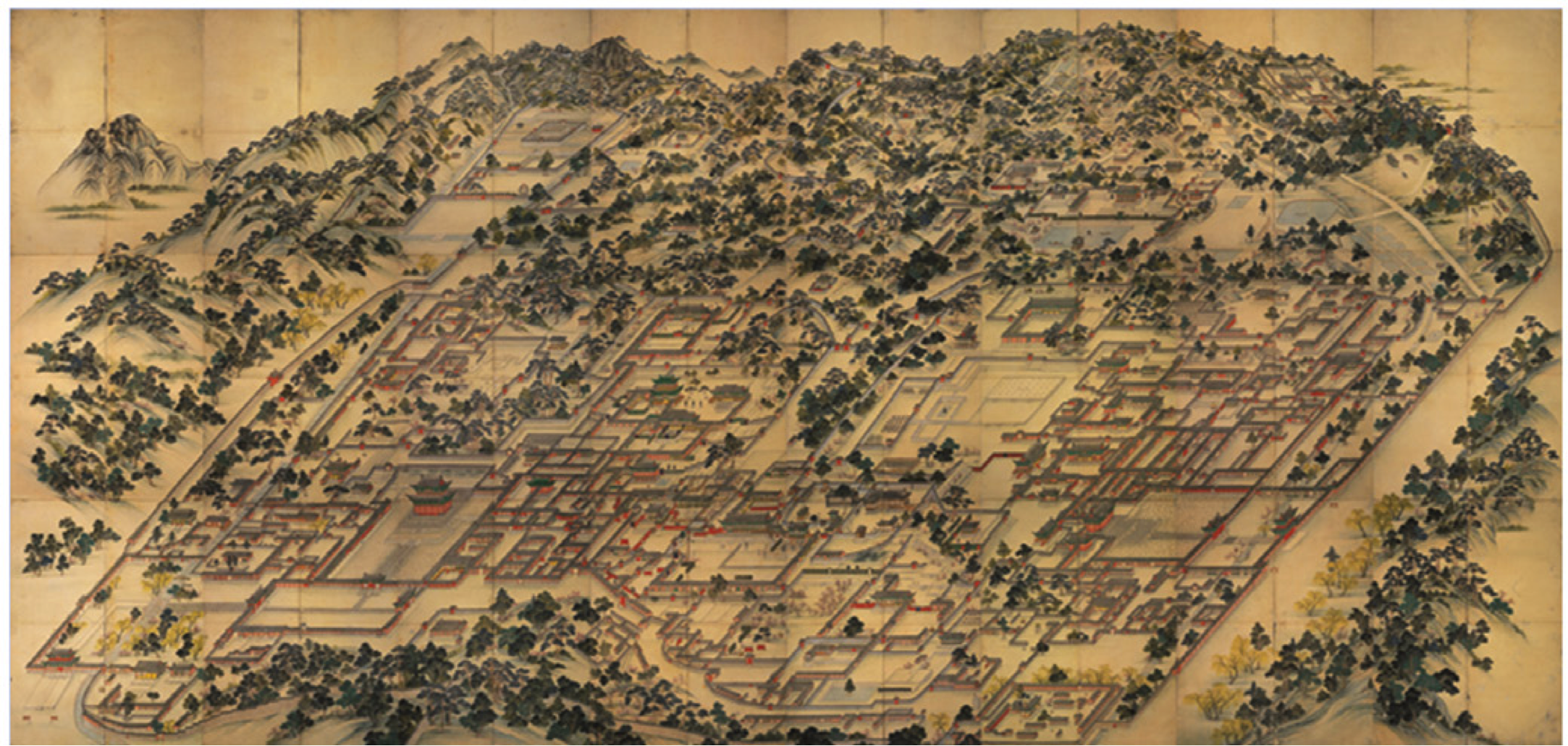

of frugality, which is modest and grave at the same time. Donggwoldo (東闕圖), or “Painting

of the Eastern Palace” The most useful material in gaining an understanding of the overall

composition of Changdeokgung Palace is “Donggwoldo (東闕圖),” or “Painting of the Eastern Palace,” which is

dated to around 1828. Like an aerial photograph, it gives a clear view over the

whole palace area. In the form of a 16-panel folding screen, measuring 576cm

long and 273cm high, “Donggwoldo” shows not only every pavilion, hall, gate,

and wall of the pal- ace surrounded by mountains and hills, but also building

sites, astronomical facilities, streams, bridges, ponds, rock formations,

potted plants, crockery terraces, trees, and flow- ers, all of which are

realistically and clearly depicted in fine brushwork. The special beauty of Changdeokgung and the nature of its spaces can be

seen in the countless corridors and courtyards that form enclosed spaces, the

pavilions in the gardens, and the roofs of the high gates that break up the

monotony of stone walls and corridors, as descri bed in “Donggwoldo.” The

painting shows how well the architecture harmonizes with the natural

environment, how the buildings are set on the land, how the buildings,

corridors and walls combine to form courtyards and the boundaries to external

spaces, how such courtyards and external spaces are brought together to form

bigger areas, and how the structures scattered throughout the Rear Garden

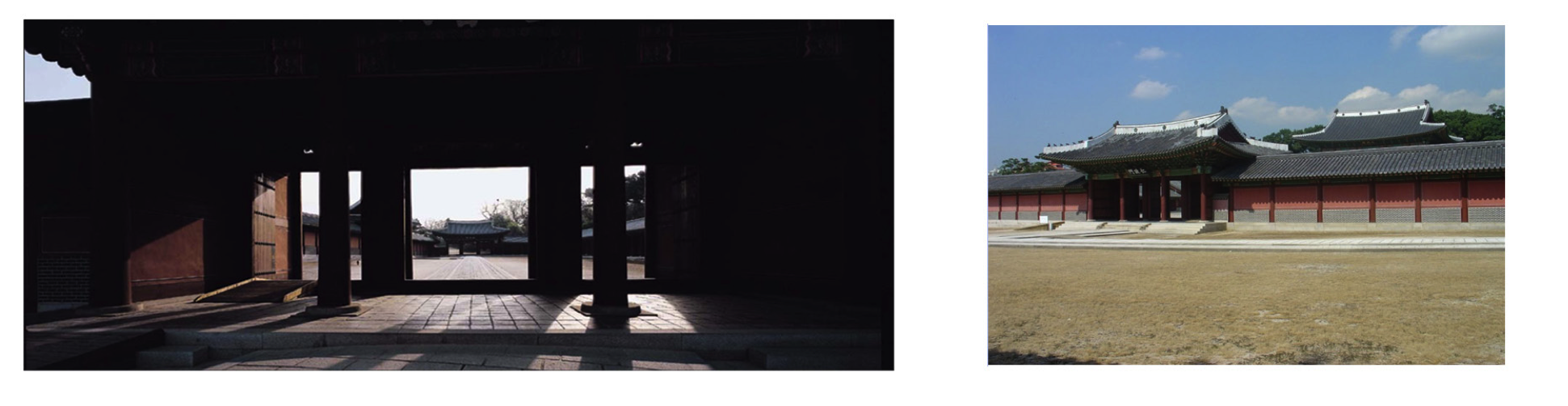

complement each other without upsetting nature. The Rear Garden of Changdeokgung Palace is where the king retreated from

the pres- sures of ruling the nation and sought peace in which to study and

cultivate the mind and spirit. It also served as a hunting ground at times or a

place to practice martial arts. Sometimes the king installed an altar and

performed memorial rites to the ancestors in the garden and at other times he

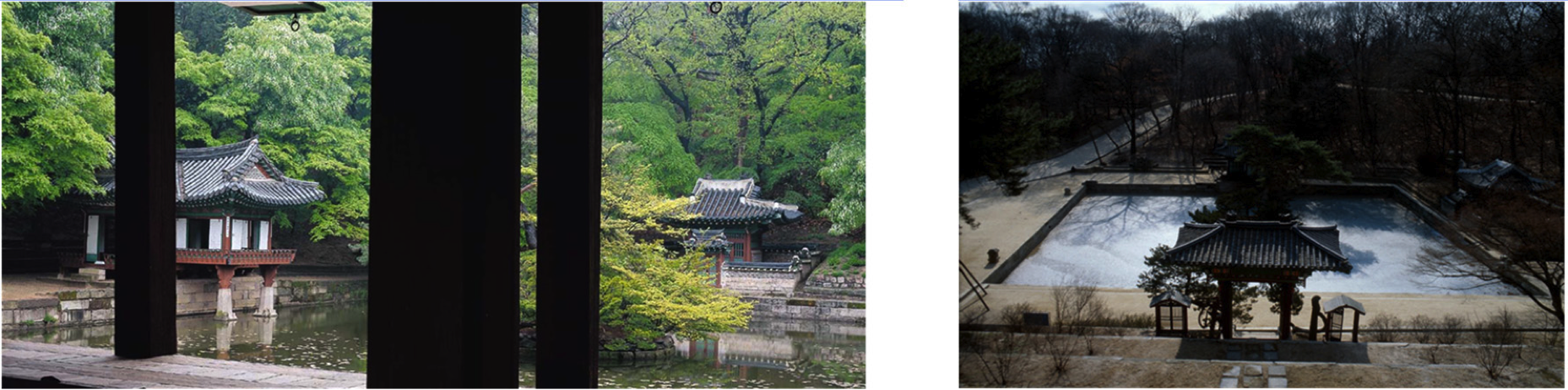

held feasts for his courtiers and officials. The Juhamnu (宙合樓) Pavilion

area, which was formed by King Jeongjo (r. 1776-1800), is hailed as the part of

Changdeokgung displaying the most exemplary use of space. The build- ings in

the Juhamnu area show the distinctive features of Korean architecture in terms

of layout and the way nature is incorporated into the spaces created. As with

much Korean architec- ture, they are designed to frame an attractive view from

the inside. The buildings in this part of the palace are so well harmonized

with the natural environment that the architec- ture, gardens, and nature are

not separate things but form a beautiful whole. Buyongji Pond (芙蓉池) in front of

Juhapru is a square pond with a small round island in the middle bearing a

handsome pine tree. It reflects East Asian ancient cosmology under which heaven

was considered round and the earth square. Buyongjeong (芙蓉 亭) Pavilion is

perched at the side of the pond facing north with its front pillars dipped in

the water. Looking out over the surrounding area from this pavilion, which has

a cross- shaped plan, the scenery and buildings in the vicinity seem to rush

forward into view. To the east of Buyongji is Yeonghwadang (映花堂) Pavilion where the king held banquets for his

officials or practiced archery. To the west of the pond is a small pavilion

housing a stele erected in 1690 commemorating the construction of four wells

during the time of King Sejo. All the buildings around Buyongji Pond seem to face each other, creating

a space that shows the distinctive characteristics of Korean architecture. As

with much Korean archi- tecture, the buildings here have been designed to frame

an attractive view of the out- side from the inside, using the principle of

chagyeong (借景), which means

“borrowed scenery,” to bring the outdoors inside. The core of any space in

Korean architecture is the principle of following the natural lay of the land

to bring the architecture and scenery together as one, as exemplified in the

Buyongji area. The buildings surrounding Buyongji Pond in the Juhamnu area differ in

size and func- tion but all look out over the pond. Though each building has a

different orientation, the pond serves as an element that ties them all

together, creating a unified whole. On the surface of the pond the sky is reflected, the trees are

seen upside down and the roofs of the surrounding buildings float along the

water. In this way heaven, nature and architecture are gathered in the pond.

Buyongji is thus the core of the nature, space, and architecture of the Juhamnu

area; it is the visual focus and the element that elevates the quality of

everything around it. It not only enables nature and architecture to show each

other off to advantage, but serves to create a gracious space, a space without

ten- sion. Thus, Changdeokgung Palace is more than just a palace to most Koreans.

The archi- tecture and spaces created embody the nature of the Korean people,

and the ancestors’ attitude to nature. The palace strikes a chord in the hearts

of those who visit because of the intimacy of the spatial arrangements and the

beautiful harmony between the archi- tecture and the natural setting. 3. Rethinking “Cultural Landscape” As shown through the cases of one and two, from early on Koreans

developed a philosophy of architecture as one with nature, and ultimately one

with human beings. Under the Confu- cian system of thought, architecture formed

in this way represents the unity of “sentiment” and “scene,” where the subject

of the “sentiment,” or aesthetic appreciation, and the object, or the “scene,”

are completely in accord with each other. The unity of sentiment and scene represents movement beyond the state of

projecting the individual world view on the object to reach the state of

expressing the world view sought by the individual in the projected object.

This association of architecture with human virtue leads to the state of unity

of heaven and humankind, where the subject and object are one. This is the

highest state, which enables architecture and nature to achieve harmony and

coexist. It is mainly maintained that “cultural landscape” is, in general, the

artificial landscape made by people who has a certain culture, nonetheless, the

nature itself can constitute the part of cultural landscape. For this reason,

“cultural landscape” could be changed through time, be- cause it is a part of

expression of people’s world view or idea on the land. Cultural landscape is

associated with the people of the past, that is, it is not the created

landscape at present time. In other words, cultural landscape as a heritage is

a sustainable landscape and symbolic, repre- senting the traditional world view

of the people from the area. In sum, Confucian world view of the interaction between humankind and

its natural envi- ronment as reflected on the architecture of Korea will

embrace the diversity of “cultural land- scape.”

- JOURNAL

- CONFERENCE

- WORKSHOP

- EXHIBITION

- PUBLICATION

- OD BRAND

- ACTIVITY

- NEWS