Abstract

We can come up with a paradox that it is

crucial for a certain region to allow a situation that will exclude foreigners and

isolate itself from outside world to a certain degree for the sake of creating

a unique architectural style that will be born only in the region.

Each region

has its own distinctive climate and natural features, which affect the

formation of architecture in some points. On the other hand the architectural

style of a region is hugely influenced by the religion, culture and the way the

culture’s existence, which are exclusive to the region. In addition, a great individual (= a closed

system) would greatly incorporate the historical context and contemporary

features and propose universality that leads to the world while rep- resenting

the natural features of a region.

It is said that no arches exist in the

architecture of the Inca Empire. It is not fair, however, to simply think of it

as not civilized one that was lack of information and technology from the

standpoint of the Western culture because we can say that Machu Picchu is

creative due to that reason. In ancient times, the culture and

civilization of Rome and China expanded as much as to cov- er almost the half

of the world, becoming the origin of globalism in classical meaning; however,

the wave of the Western culture did not reach Angkor Wat, Candi Borobudur as

well as the Inca. As the Germanic peoples invaded the north

east part of Europe after the Ancient Rome was destroyed in the fifth century,

the non Roman architecture such as gothic style from “the Goth” appeared as a

new civilization in the Latin Empire including France that had been proud of being

the descendant of Romans. However, Italia or Southern Europe would not want to

fol- low such directions although gothic style had introduced new technologies

such as building soaring spires. The Western culture flowed in North America,

Latin America, Asia and Africa (in other words, almost entire world except the

West itself ) and dominated their natural features for about 400 years from the

discovery of America by Christopher Columbus at the end of the 15th century

until the 20th century came. The center of Rome had been moved to Istanbul and

managed to survive for another 1,000 years until it was invaded by Saracen at

last in the 15th century. The Renaissance is believed to be the movement of

reviving the Roman tradition that had been at the verge of being perished but

managed barely to preserve by the creativeness of several geniuses while it was

stoutly absorbing such advanced civilizations under the surface of such

formidable foreign cultures as gothic or Saracen. The Roman architecture was systematized in

École nationale supérieure des beaux- arts, France and applied to the great

renovation of Paris as the architectural language of Neo-Clas- sicism during

the middle of the 19th century. Since then, the Neo-Classicism began losing its

flexibility and, finally, came to an end from the inside of Europe. New

technologies including reinforced concrete and steel-frame structure were

incorporated and a new globalism called modernism has spread into the world via

a number of unique and creative skills and means discovered in the early 20th

century. The current architectural civilization of the

major cities in the world has been placed on the extension of such modernism

and come to the present status leaving the issues of how to confront the matter

of “natural features”. “Natural features” are like the old painting or original

background remaining on a canvas when a painter is about to draw a new

painting. Depend- ing on whether the painter draws a new painting considering

them as pure white background or having conversation with the background by

adding new shapes and colors based on the existing ones, it will result in

pretty much different consequence. Some say that the contribu- tion and sin of

the 20th century’s architecture are the destruction of natural environment,

tra- ditional streets, etc; however, I presume that the common aspect of such

faults would be the attempt itself to draw something on a “white” canvas rather

than something that limited to the area of architecture. However, the natural features, which are

considered to have always been exposed to the risk of being destroyed by such

globalism in terms of classical meaning, is thought that is in- compatible with

globalism and could be the foundation of the pluralistic view that is regarded

as the end of anti-globalism. On the other hand, isn’t it also a

narrow-minded way of thinking to simply denounce glo- balism as the destroyer

of natural features? Due to this matter, the issue of “natural features” could be taken into consideration and

re-vitalized again paradoxically. If there is a locality that has been

completely severed from the surroundings, it would be understood as the center

of a small universe rather than being called locality. Therefore, it is possible to build another

hypothesis – “Globalism reminds us of natural features”. Perhaps, the answer

will be the world where both exist together rather than a world where one of

them has disappeared. It is likely to say that it resembles “an ocean and fish

that live in the ocean”. In the ocean, there are several tidal currents as well

as daily tides that occur globally due to the movement of the moon. The

Kuroshio Current carries coral and plankton from the southern region and moves

up all the way to the Korean Peninsula and Japan. In gen- eral, there are

“oceanic fishes” such as oceanic bonitos or tuna fishes that live in such tides

and have rather wide cruising radius; on the other hand, there are shore fishes

that move within a range of 50 Km living under rocks. The former is global

fishes while the latter is fishes living under natural features. Although these

do not seem to have relationship, in fact, obvious rela- tionship between these

two cases can be found, affecting each other via the food chain. Whenever we mention [internationality] or [universality],

it has been misunderstood to indicate “oceanic fishes” until now; however, as

you can see if you go to a fish market, tuna fishes or sardines are not the

only fishes that are traded in a market. There are shore fishes such as rock

fish that can be found in any fish markets in the world such as fish markets in

Greek, Pohang in Korea or Tsukiji in Japan. Although we may lose the global

tides as a frog in the wall knows nothing about the great ocean if we

completely shut ourselves in a region, it does not mean that an ability to move

around the world widely and to adapt oneself to any place will automatically

become the bases to create [universality]. Losing the capacity to see “natural

fea- tures” can be equivalent to losing the root of the culture. Given that natural features are not connected

to nationalism in a narrow sense but contain the universality that connects to

the world, the light leading to the future in the 21st century will begin

shining from here. Natural Features

and Globalism Both the natural environment and the city can

be recognized as a patchwork of differ- ing elements and areas adjacent to each

other. The resultant fragments and fields create a complex maze of boundaries

and conflict. On the other hand, if we accept Structuralist ideals, the city

can be regarded as a kind of “entire system” like the human body. Given such

disparate interpretations, the way we go about recognizing the city must have

much to do with our cognitive models. If we take the former model of the city

and natural en- vironment as being made of conflict, then it can be said that

human beings have used 3 methods of aleviating those stresses I here call

“alienation”. Alienation = discord: a situation created by

the coexistence of two incompatible elements. Examples include discord in

color, scale, angle, culture etc.. 3 Methods of aleviating

alienation: Separation: ( e1, e2 ) -----> (e1 / e2

)

Refusing the adjacency of incomaptible elements. By putting up barriers or

leaving a great distance between them they have no contact. Assimilation: (e1, e2) -----> (e1, e1)

One

or more element is forced to assume the identity of another element. Mediation: (e1, e2) -----> (e1 /M/

e2)

Placing a mediator between 2 discordant elements. The presence of the

mediator does not change the quality of either of the two elements in character

or form. It is possible to have several kinds of mediators at once. It may be said that this is just an extension

of an analogy applied to human society. However, it can applied to the city and

the natural environment where we regard them as a series of conflicting areas.

From the example of putting up hedges between houses to the example of zoning

theory the idea of separation emerges. Examples of assimilation are clear when new

buildings are expected to meet minimal expectations such as maintaining an

eaves height similar to adjacent properties or to ad- here entirely to a set

style. In assimilation there is always a kind of power at work. Whether it is

economic, political or cultural it tends to force one of the components to

follow the other. This is normally a method of preventing new situations of

alienation from arising. However, in this there is the risk of creating another

kind of alienation; one where the new destroys the parts of an otherwise

harmonious patchwork. Among the three methods, media- tion has the

most promise in the mod- ern setting. It is more subtle and ver- satile in its

application. Mediation has two categories, the physical and the semantic.

Physical mediation is dem- onstrated in the balancing of difference between

things like angle, shape, color, and scale. Semantic mediation occurs in

clarifying differences of meaning and cultural.We should expect more devel-

opment in the study of mediation concerning modern cities where physi- cal and

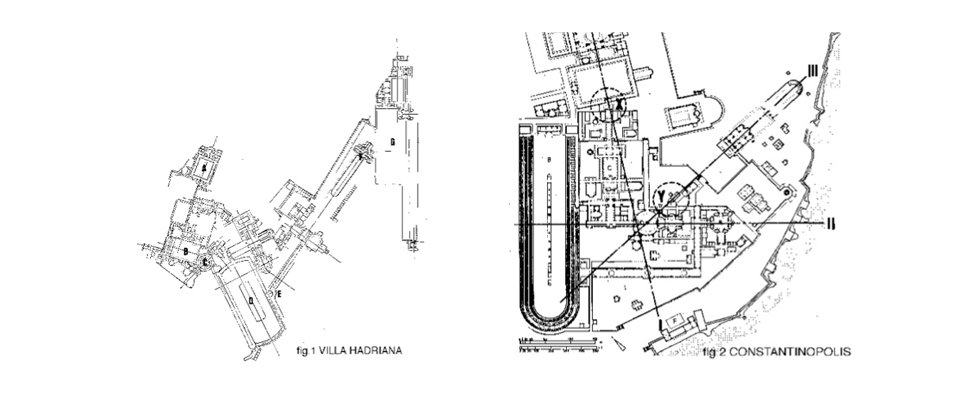

cultural entropy increases con- stantly. An example of mediation can be found in an

analysis of cylindrical forms in plans of ancient Rome. Hadrians Villa,

although not a city itself, has a quality of organization similar to that of a

Ro- man City (See fig. 1). It is composed of differing angular systems. One

group follows an axial system while others are angular. Where the two collide

the composition becomes a series of sev- eral angular fragments. At any

specific point of meeting there always appears a round architectural type as a

physi- cal mediator between the opposing angles. These round types enable the

coexistence of many different angles to function as a system or patchwork.

In Constantinopolis on the other hand, there

is another round type; one which acts at all times as a center point where many

axis meet (See fig. 2). Under the rule of Constantinous Constantinopolis became

the first Christian City. Here, the round element began to play a more sacred

role operating as a unique center integrating the whole city through

centralization as a compositional tool. Historically, before Constantinopolis, round

form was typically used as a mediator aleviat- ing potential physical conflict

between disagreeing compositional forces. Interestingly, afterward, round type as a

physical mediator was rapidly replaced by round type as center point. From the

change in ideology, I could interpret the parallel change in the physi- cal

meaning of round type. The city as well as the natural environment

is full of conflicts created on the boundaries between different patchworks.

Yet these conflicts evoke the emergence of the new related- ness between

alienated fields. Even in the topics of Form and Function, we are now entering

the new era of “Form and Function are mediated”. From the word “Form follows

Function” that represents the begining of the 20th century.

I believe that as

“mediation” is the only notion of today that could regard all those conflicts a

positive energy to turn a harsh chaos into a more fruitful multiplicity. Sun Moon Lake Administration office of

Tourism Bureau

—A landform for dialog between the human being and nature This is one of the projects from an

international competition held in Taiwan in 2003 for four representative sightseeing

locations in Taiwan called the Landform Series. It is a project for an

environment management bureau that houses a visitor center in the Sun Moon Lake

Hsiangshan area. The site just touches the narrow inlet

extending almost south-north at its northern tip, has a narrow opening facing

the lake-view direction, and extends relatively deep inland along a road.

Looking towards the lake, the lake surface looks like it is cutout in a V shape

as mountain slopes close in from both sides. That is, although the site is for

the Sun Moon Lake Scenery management bureau, it doesn’t have a 180° view of Sun

Moon Lake as can be enjoyed from the windows and terraces of the hotels

standing on a typically popular site. In most cases with sites like this, the

building is positioned on the lake side to secure the greatest view possible,

and thus the inland side tends to become a kind of dead space. As the basic

policy for the design, my first aim was to propose a new model for a

relationship between the building and its natural environment while preserving the

surrounding scenery and keeping the inland area from becoming dead space. My second priority was to address the

disadvantages of the site whose view of the Sun Moon Lake is not necessarily

perfect, and to draw out and amplify the potential advantages. `One way to

solve the first problem was to pursue a new relationship between the building

and its surrounding landform. Since long ago, buildings have generally been

built “on” landforms, but there have been cases in which they have been built

within landforms, such as the early Catho- lic monasteries of Cappadocia and

the Yao Tong settlements along the Yellow River, and there have also been such

classics as Nolli’s map that considered the building as the ground which can be

curved or transformed, similarly to the landform, in a conceptual sense. Due to

the fact early modernism negated in totality the methods of

self-transformation—including the poche method that belonged to pre-19th

century neoclassicism in particular—and demonstrated an inability to adapt to

the complex and diverse topography in such areas as east Asia, I believe that

20th century architecture actually gave rise to the phenomenon of land

development projects that “flattened” mountains, an approach that is almost

synonymous with the destruc- tion of nature. In fact, the very key to li s each, to create

a sense of dynamism that leads to the lake sur- face. Moreover, I set up a

near-view water basin in contrast with the distant-view lake surface to enhance

the water surface effect by mirroring the distant view upon it. The fact it is

only possible to view the lake surface distantly from a relatively narrow angle

means that the site— fortunately free of nearby buildings—is surrounded 360° by

a lush sea of trees. I saw this as the second undulating surface and opened up

the upper part of the building by greening it to create continuity with the

natural surroundings. These two surfaces—the union of the lake and water basin

surfaces, and the resonance of the building’s greenery on the upper part with

the surrounding undulating sea of trees—are connected via the tunnel-shaped

diagonal path that cuts and penetrates through the interior of the building,

and through the slopes carved into the building like mountain paths, to create

a multitiered landform.

This

half-architectural and half-landform project is conceptualized as a stage

setting to bring out and amplify a hidden dimension of the scenery and

environment of Sun Moon Lake, and at the same time create a new dialogue

between the human being and nature that provides another new dimension to this

area.